|

| Insight into the dream-state |

Recently Chris

Knowles made a very interesting observation about commercials. In a dialogue with Alan Green on

the Always Record podcast he was discussing the preferences of television

viewers and what it is about shows that viewers find unacceptable. Then he referenced commercials:

That

was something I was really struck with watching the commercials – how this

world that exists on television commercials just seems so unrecognizable from

the real world. It’s creating this

utopian vision that just doesn’t exist anywhere and everything is this sort of

happy-faced, singy-songy world now in these commercials. I think they have some sort of a narcotic

effect. They tend to numb people. Even

the commercials themselves are an escapist form of entertainment, rather than

simple advertising.

I love this idea: something commonplace yet ominous. The constancy of ads is a good thing – the

drug is always there steeping us in its actual, subtle message. Is this message something that pacifies

people? Are people really being manipulated

by advertising?

Recently I started watching the documentary The Century of the Self,

which looks at the genesis of the contemporary advertising regime. Freud’s nephew Edward Bernays was

instrumental in developing advertising that appealed to people’s subconscious

drives – mass psychology as a way to make money for clients. Political thinker Walter Lippmann is

portrayed in the film as arguing “that if human beings were in reality driven

by unconscious irrational forces then it was necessary to re-think

democracy”. Bernays embraced this idea

of Lippmann and suddenly “a new way to manage the irrational force of the

masses” was born.

In the documentary, historian of public relations Stuart

Ewen says of Bernays and Lippmann:

Both

Bernays’ and Lippmann's concept of managing the masses takes the idea of

democracy and turns it into a palliative, turns it into giving people some kind

of feel good medication that will respond to an immediate pain or immediate

yearning but will not alter the objective circumstances one iota. The idea of

democracy, at its heart, was about changing the relations of power that had

governed the world for so long; and Bernays' concept of democracy was one of

maintaining the relations of power, even if it meant one needed to stimulate

the psychological lives of the public. And in fact, in his mind, that is what

was necessary. That if you can keep stimulating the irrational self then

leadership can go on doing what it wants to do.

Right there is Knowles’ narcotic effect, built in from the

first days of contemporary advertising. “Stimulating

the irrational self” – chilling. In

today’s world, though, it is even scarier.

The contextual backdrop against which Knowles made his statement is one

of seemingly darker motives. Advertising

becomes more than simply a tool for turning people into docile consumers in an

ever more affluent world. These days there

is uncertainty in the air. An election

year. People still struggling financially

even though are economy has putatively

recovered. Could Knowles be picking up

on a step-up in the rhetoric?

I have to say thank you to the world of academia (rare for

me to say these days . . .). In a

synchronistic fashion I recently came across the work of communications

professor Sut Jhally. In his own words:

My

modest claim is that advertising is the most powerful and sustained system of

propaganda in human history and its cumulative cultural and political effects,

unless very quickly checked, will be responsible for destroying the world as we

know it. [...] Those individual ads carry a very powerful single message, a

unifying message.

Jhally addresses

Knowles view of the utopian being present in advertising:

What

advertisers have to do is to link up what keeps people happy with the things

that they have to sell, which are objects. That's the falsity of it. What's

real about advertising are the dreams that it recognizes in the population. And

that's why advertising is full of adventure, it's full of independence, it's

full of sex, it's full of family, it's full of social relationships. It's full

of meaningful work.

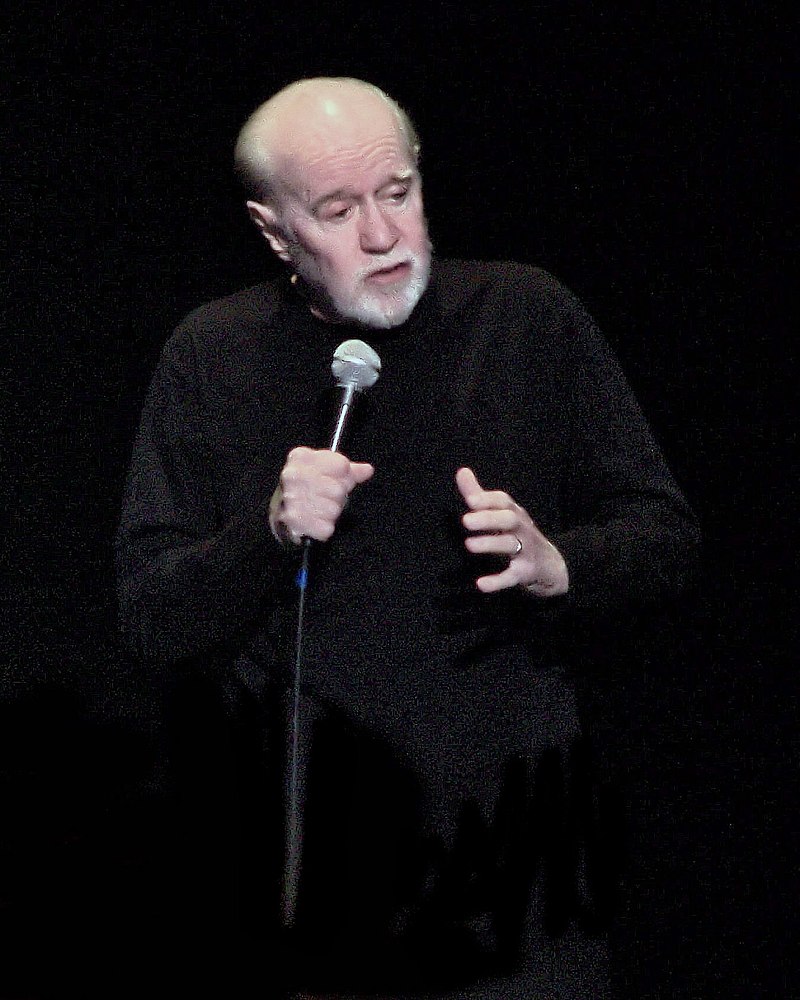

| Sut Jhally |

So what do we do?

Jhally is optimistic of change – you have to be, he believes. Change will come through activism. Through people fighting back. He believes that average people, on their own,

would understand the need for political change.

The advertising world has to overcome this innate rational state. It is a costly effort:

Why

do corporations, why do advertisers, why do media have to spend billions of

dollars every day to convince us of these things? If the game were over, if

there were no possibility of change, then why would they keep doing this day

after day after day? And why would they go out of their way to make sure that

no other idea gets into the minds of the population? They have to do that

because they know that if they don't, then the world will change.

I have to say, when I watch commercials I couldn’t agree

more with Chris Knowles. I feel the

narcotic of advertising had increased in its strength. The manipulative intentions of commercials become

more obvious when you view them through the lens of suspicion.

The dreamer needs to awake.

The “feel good medication” must be rejected.